Introduction

Seemingly everyone in my network has been busy the last few weeks reading Secrets of Sand Hill Road: Venture Capital and How to Get It, the highly anticipated book by Andreessen Horowitz partner Scott Kupor that published last month. By all accounts, it’s an excellent guide for helping entrepreneurs and other onlookers understand the practicalities of the venture capital business. I look forward to reading it soon.

I, on the other hand, have been focused on a very different type of book on the venture capital industry. VC: An American History is a fascinating tour of the genesis and evolution of the venture capital business, spanning more than 200 years of development. The book was written by Tom Nicholas of Harvard Business School and released just one day before Secrets of Sand Hill Road. I have been eager to get my hands on this book since first learning about it months ago, and I’m happy to say, it didn’t disappoint.

Nicholas produces what any good historical inquiry should: a detailed documentary of how we got to where we are, an illumination of key lessons learned along the way, and a clear framework to guide the reader’s imagination into how the future may unfold. For me, this is the real genius in studying history: it exposes weaknesses in the current state of things, highlights tested problem areas, and provides signposts for improvement. Unfortunately, too many in the innovation economy today ignore the many useful lessons of the past. In my view, understanding the past is critical to understanding the present and the future. History is a forgotten innovation hack.

While the popular version of the genesis of venture capital takes place right after World War II with the advent of American Research and Development Corporation (ARD) in Boston in 1946, Nicholas goes back further. Much further in fact. He demonstrates that ARD was just one piece of many in an evolutionary process of dynamic capital markets going back at least a century, and that ARD’s founding was a culmination of practices discovered in early-stage risk capital and long-tail investing developed through trial-and-error in other contexts.

“Across all these stages, a major theme of this book has been the importance of historical perspective. History matters because it helps to explain how things came to be what they are. Lines of continuity or change can often be traced from the past to the present. The venture capital industry was not an isolated mid-twentieth century invention, but rather a continuation of a deep-seated tradition in the deployment of risk capital in the United States going back to early instances of entrepreneurship. Historical perspective can also discipline a better understanding of future directions and possibilities. In particular, it can illuminate several challenges the VC industry faces today.”

More fundamentally, Nicholas ties the principal function of venture capital—systematically producing outsized returns on long-tail distributions of startup companies in emerging high-tech industries—to other episodes in American economic history. He does this by breaking down the history and development of the venture capital industry into four phases. I’ll review each of these phases in this post.

This article is my summary of Nicholas’s work. Because the book goes deep in a number of key areas, I’m leaving out a lot of detail. The only way to absorb that is to pick up the book and read it for yourself. The purpose of this article is to synthesize my own reading of the book and to encourage a broader audience to buy a copy and do the same for themselves. What started out as a simple exercise in describing the book’s main findings, quickly turned into the more than 13,000 word essay below. It is mostly a book summary, but also includes some of my own analysis and commentary. I think you will find the time spent reading Nicholas’s hard work well worth the reward. I hope the following essay will encourage you to make that investment.

Early Risk Capital Investing (early-1800s to 1940s)

Whaling Ventures

Artist depiction of an early 19th century whaling expedition.

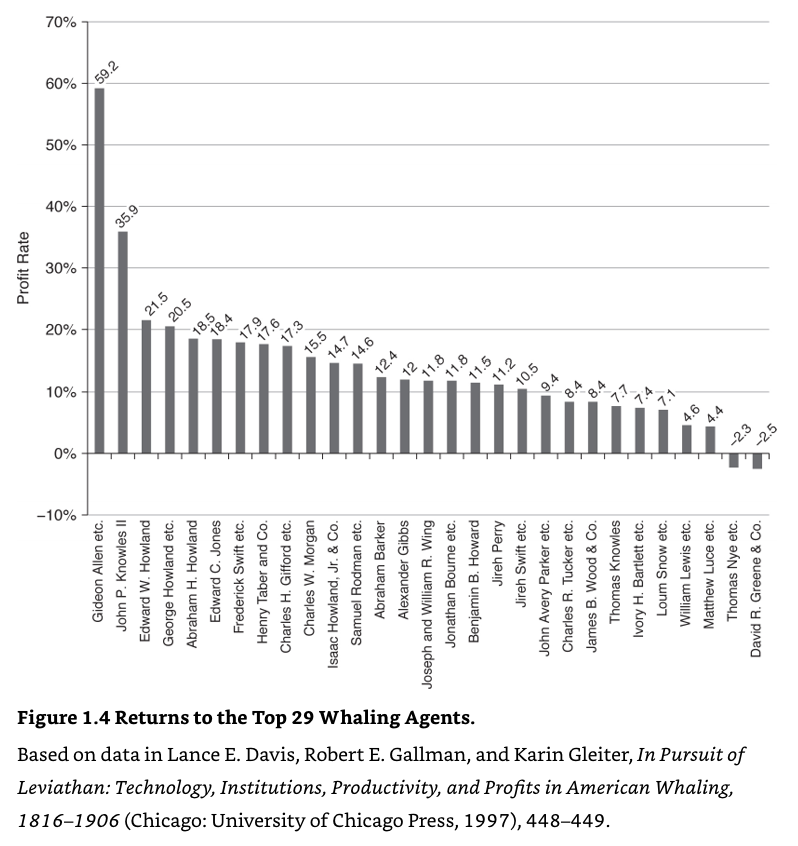

The first phase begins with the early-to-mid 19th century whaling industry in New Bedford, Massachusetts. It featured three key complementary factors that are remarkably similar to key aspects of the venture capital capital business today:

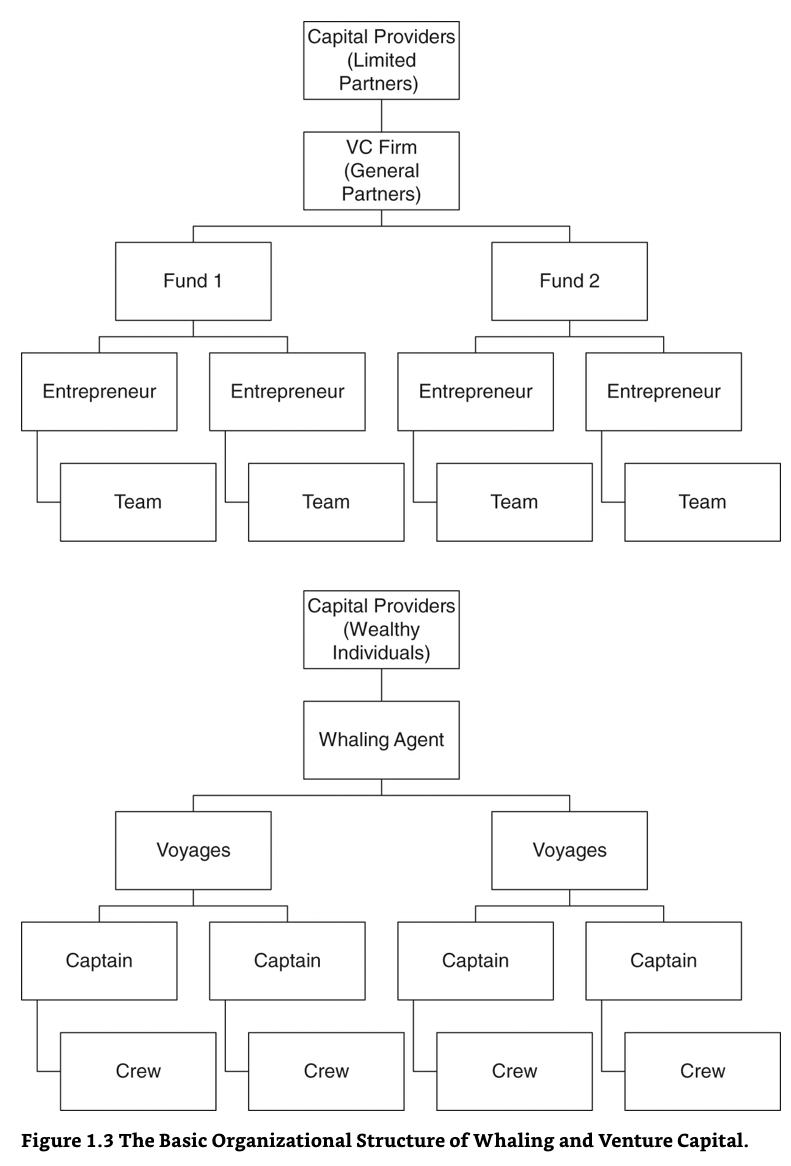

Organization: the whaling industry was organized through an agent-centric model, where intermediaries who had developed specialized human capital (whaling agents) pooled capital from wealthy investors to fund expeditions—similar to the general partner / limited partner relationship seen in modern VC.

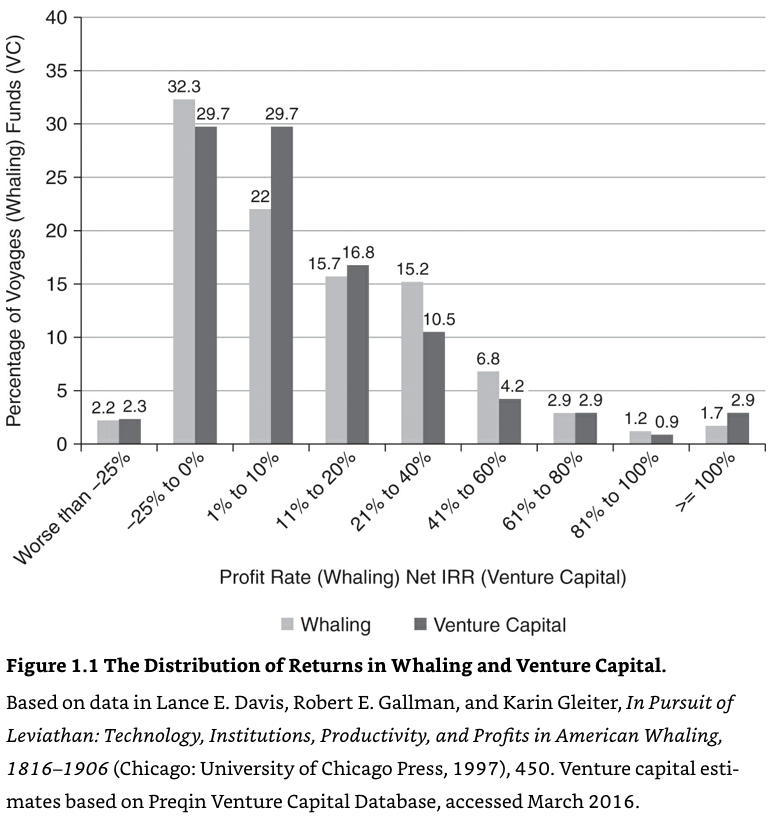

Long-tail returns: whaling expeditions were high-risk (requiring significant up-front capital) yet potentially high-reward (successful voyages could fetch sizable profits)—producing long-tail returns with many failures offset by a small number of very large wins.

Incentive structures: whaling expeditions were structured around a strong alignment of incentives through performance-based equity. Whaling agents worked on a “two and twenty” model seen in modern venture capital (in fact, this may be where it originated). Vessel captains (“founder / CEO”), first, second, and third mates (“co-founders / CXOs”), and crew (“founding team”) were given “lay”, which functioned as modern day equity that netted a share of profits in the event of a successful whaling expedition (“exit”).

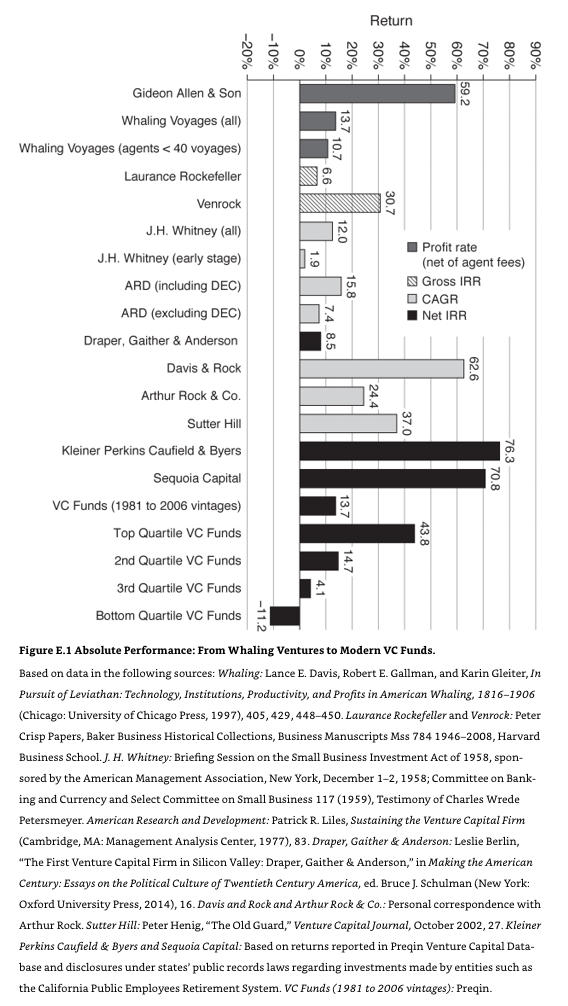

Three images from the book illustrate these points—the agent-centric organizational structure, long-tailed returns similar to those seen in modern VC, and the high variation of performance among the various whaling agents (ie, “VCs”), also common in the VC industry today.

Early Development of Risk Capital

The Old Slater Mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, founded in 1793 by Samuel Slater (an entrepreneur) and Moses Brown (an industrialist and investor). Their partnership brought the Industrial Revolution to America, and their agreement (detailed in the book), contained many similar elements as modern-day venture capital term sheets.

As the economy shifted from merchant trade to industrial production in the mid-to-late 19th century, wealthy elites diversified investments into the new “high tech” industries of the era. From this, clusters began to emerge around textiles in New England (first in Rhode Island and then later Lowell, Massachusetts) and heavy industry during (the Second Industrial Revolution from the late-1800s to early 1900s) in Cleveland and Pittsburgh. Along with growing early-stage investments in emerging industries and geographies came innovations in financial intermediation, cash flow and contracting, and governance practices that resemble many of those seen in the venture capital industry today. Investing of this nature was still experimental, and was mostly driven by informal networks of wealthy individuals and families matched with intermediaries. Success was highly variegated.

Private Capital Entities

However, from around the turn of the century to the end of World War II, more formal models of early-stage “high-tech” investing began to emerge as “VC-like” private capital entities started being established in Boston, San Francisco, Pittsburgh, and especially New York. These entities pooled private capital across multiple investors (typically families), developed skills for due diligence and portfolio firm selection, staged investments, and deepened governance practices of portfolio companies, such as board representation and managerial expertise—once again, pioneering practices adopted by the venture capital business today.

Laurance Rockefeller

Iconic American firms like Ford Motor Company (Detroit), Eastman Kodak (Rochester), Federal Telegraph Company (San Francisco), and McDonnell Aircraft Corporation (St. Louis) were high-risk ventures in speculative industries that received critical financing and support by investors with structures very similar to modern angel, “super angel”, and venture capital today. Two active investors of the day, Bessemer Trust and the Rockefeller Brothers (led by Laurance Rockefeller), were antecedents of two prominent American venture capital firms—Bessemer Ventures and Venrock. Another, J.H. Whitney & Company, remains a leading private equity firm.

Taken together, the period from the early-19th century up to the middle-20th century can be described as one of widespread experimentation and setting the table as it relates to venture capital. Private capital-pooling entities began financing high-risk ventures, but the industry was still in its infancy. In spite of great progress, two key shortcomings remained:

Lack of scale: the supply of investment into “venture capital like” activities was still scarce, and remained limited to a small group of wealthy individuals or families. Early-stage risk capital investing had achieved nowhere near the scale that would be required to meet the growing demand for entrepreneurial finance.

Lack of returns: none of the precursors of venture capital managed to earn the outsized returns required to sustain an industry faced with long-tail outcomes. In fact, despite some individual successes named above, the industry generally didn’t return value beyond what could be held in public market equities. Rockefeller failed to return capital above a public market benchmark, as did Whitney (who shifted into later stage investing). Even the biggest successes of the era produced returns far below those seen in today’s home-runs (or even doubles and triples). But, that was about to change.

***

As Nicholas’s comprehensive and novel research of the history of risk capital in America demonstrates, the fundamentals of venture capital investing are not new. In fact, the basic function of venture capital goes back at least two hundred years to New England whaling expeditions (possibly even further). The similarities in business model, incentives, contracting, and governance between modern high-tech startups and venture capitalists, and their antecedents—such as whaling expeditions, textile mills, and automobile production, to name a few—is both remarkable and illuminating.

The Rise of ARD and the Formalization of VC (mid-1940s to mid-1960s)

The second era of venture capital in America roughly takes place from the end of World War II in the mid-1940s and stretches into the mid-1960s. During this period, the formalized model of venture capital—firms of specialized intermediaries deploying pooled investment capital into early-stage high-risk ventures that systematically produce right-skewed returns—finally came into place. This occurred through three channels.

American Research and Development

The first of these was the rise of American Research and Development Corporation (ARD). Founded in Boston in 1946 by a group of civic-minded business, academic, and public elites at the New England Council who were eager to stimulate regional economic growth through innovation and entrepreneurship, ARD is widely considered to be the first venture capital firm in the modern sense of the term. The firm is synonymous with Georges Doriot—the French-born Harvard Business School professor popularly known as the “father of venture capital”—who led ARD shortly after its founding nearly through the end in the early-1970s. However, the original brainchild of ARD was not Doriot, but Ralph Flanders—an engineer and industrialist who handed the firm to Doriot just six months after founding so he could be seated in the U.S. Senate on behalf of his home state of Vermont. Even so, Doriot would come to define the firm.

Georges Doriot

ARD’s association with modern venture capital is threefold. For starters, it was the first firm to truly leverage its investment capabilities with capital from institutional investors. Recall, the precursors to VC did pool private capital but it was primarily driven by informal networks of wealthy families and individuals, and was therefore operating on a scale that was far too small given the rapidly expanding technological opportunities at the time. The supply of capital fell well short of demand.

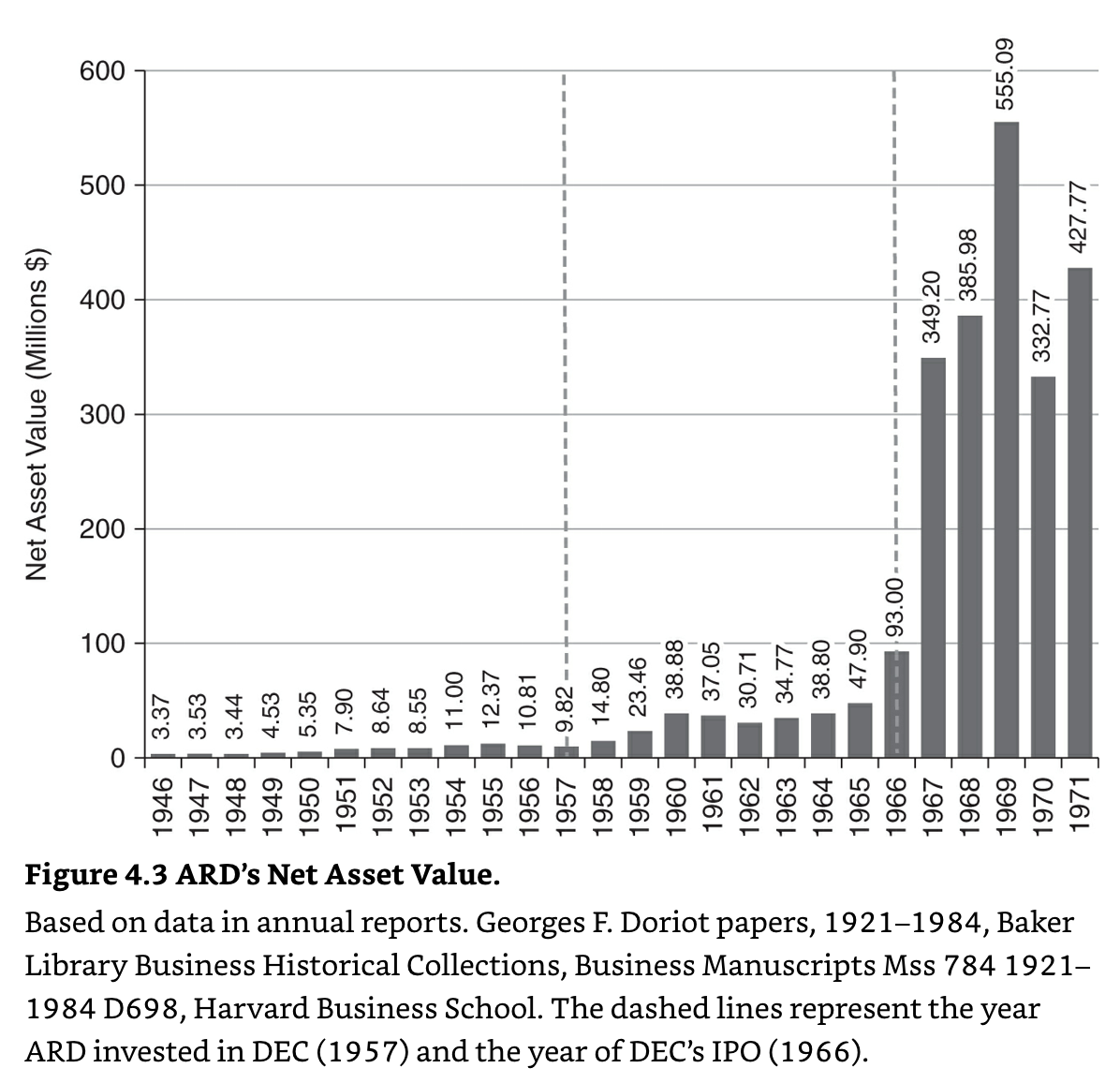

ARD’s second major contribution to the development of venture capital was its investment in Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), which validated the model of producing outsized returns through long-tail investing. In 1957, ARD made a $70,000 investment into DEC for a 78% equity stake in the company (an enormous share by today’s standards, but typical at the time). The investment was made early in the company’s lifecycle, as it faced considerable uncertainty and intense competition from major industry incumbents such as IBM. Within a decade, however, DEC defied steep odds, becoming one of the biggest successes in the minicomputer industry, and in 1966, issued shares for an initial public offering.

It is estimated that the value of ARD’s $70,000 investment in DEC in 1957 was worth $230 million nine years later in late-1968, and reached a whopping $355 million in unrealized gains by the end of 1971, or more than 5,000 times the initial investment.

ARD’s investment in DEC was so pivotal that it single-handedly turned ARD’s overall investment activities from underperforming relative to public equities to outperforming them by a respectable margin. Without the DEC investment, ARD likely would have been a failure, and it’s hard to say what the broader implications would have been for venture capital as we know it.

Two figures here demonstrate the outsized importance of DEC to ARD’s fund performance—in the first instance showing the overall dollar value of ARD’s portfolio over time, and in the second chart, illustrating its rate of return. As we can clearly see, DEC made all the difference.

And that to me is the biggest takeaway from the ARD experience—the financial return produced by a single company represented a proof-of-concept for the venture capital industry to flourish.

ARD’s third major contribution is that its structure—a closed-end fund, with fixed shares that could be traded on a secondary market—highlighted the inadequacy of such an organizational form, and called for a new model to emerge. This particular structure put ARD at a disadvantage from a regulatory, tax, and recruitment perspective. ARD’s structure prevented it from raising funds from particular investors, the investors that could invest faced unfavorable tax treatment relative to alternatives, and the investment professionals the firm employed could only marginally participate in the upside of successes (like DEC). In fact, it is widely believed that the challenges presented by this structure ultimately led to ARD’s downfall. By the late-1960s, ARD looked nothing like a venture capital firm, and by the early-1970s, it wound down.

Limited Partnership

The second major development during this era of venture capital was the gradual embrace of the limited partnership structure, which was first adopted in the United States in 1822 in New York and modeled after the French société en commandite. This was historically significant because it represented the first time in history that a statute of any country other than Great Britain had been adopted in the United States.

The limited partnership structure provided five key advantages for the pooling of risk capital.

Limited liability: quite obviously, the liability of passive investors (the limited partners investing in venture funds) was limited.

Tax advantages: the tax treatment for pass-through entities was preferential compared with the corporate structure of funds such as at ARD.

Equity compensation: regulations governing corporate structures like ARD stipulated that employees could not hold equity in their portfolio companies, which meant that in the case of a successful exit, fund managers would not have access to the upside. But, limited partnerships were permitted more flexible (and generous) compensation schemes for investment professionals.

Fixed duration: limited partnerships are of a fixed term (typically between seven and ten years), which puts an emphasis on deploying capital and generating payoffs in a shorter period. For investors, getting your money in and out quickly is an attractive feature. At a macro perspective, the net impact of speed to exit is at least up for debate. At minimum, it has shaped the incentives around what types of companies get funded (and started).

Regulatory compliance: in addition to the flexibility around general partner compensation mentioned earlier as well as some others, the limited partnership was not subjected to the same regular reporting requirements that investment structures like ARD had to comply with. As one leading VC at the time remarked, the strategy was “to get the money in and report on it as little as possible.”

Despite these advantages, the adoption of the limited partnership structure to deploy risk capital was slow, but according to Nicholas, was unsurprisingly accelerated during the 1950s and 1960s “tax shelter era”. Much of the influence of the limited partnership structure for venture capital came from oil and gas exploration.

William Henry Draper, Jr.

The limited partnership structure wasn’t introduced into the venture capital industry until the formation of Draper, Gaither & Anderson (DFA) in Palo Alto in 1959—a $6 million fund (about $50 million today) that invested at what would be considered Seed or Series A today. Although DFA was short-lived, it was important in setting the stage for risk capital intermediation in a venturing context and in establishing management fee and profit-sharing structures used to this day, and is considered to be the first true Silicon Valley venture capital firm. Two other VC firms formed not long after DFA—Greylock Partners and Venrock Associates—had much greater success, further validating the venture capital model and encouraging its wider adoption.

Small Business Investment Companies

The role of the federal government in developing the venture capital industry looms large from the late-1950s through the mid-1970s. Three major policy interventions (one direct, two indirect) had the effect of increasing venture capital deployment through the supply (limited partners and venture capitalists) and demand (entrepreneurs) channels.

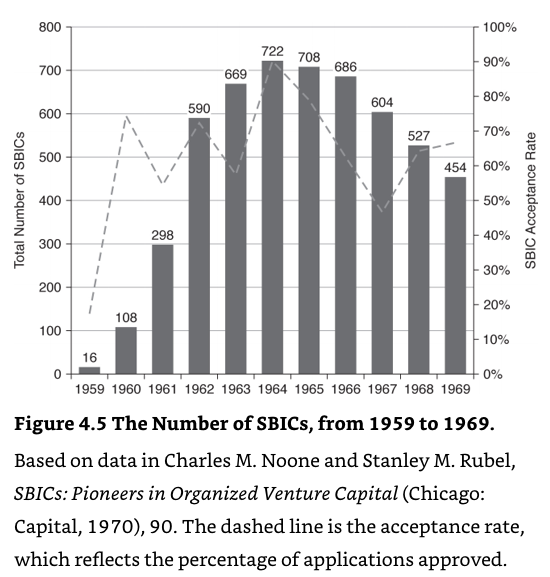

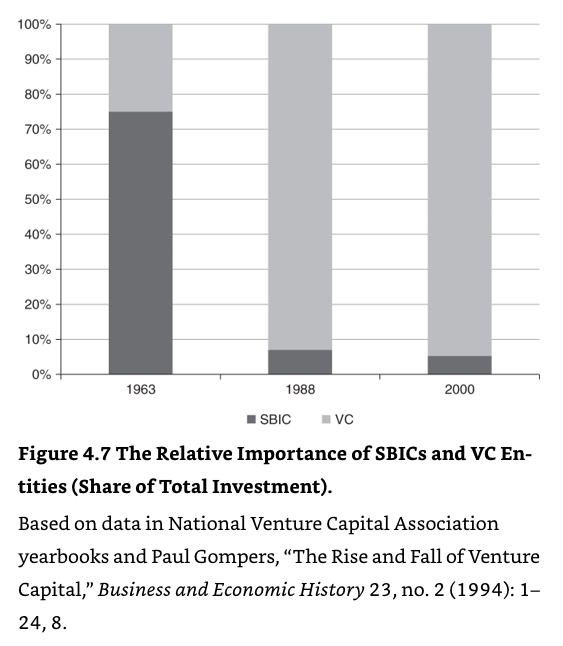

The first of these was the Small Business Act, passed in 1958, which funneled public funds to qualified small business investment companies (SBICs). SBICs acted as venture capitalists by leveraging private capital they had raised with public funds that were available under attractive borrowing terms (the government didn’t ask for carry, just its money back) and preferential tax treatment. In exchange for these generous benefits, SBICs were forced to comply with strict regulatory oversight, which made them unattractive for some investors (such as ARD, which was the first company offered SBIC designation but declined).

As the data show, the growth of SBICs was slow at first, but peaked quickly and then tapered off just as fast. SBIC returns were mostly unfavorable and interest from new entrants waned. Even many of the larger, better performing firms returned little more than the S&P Composite index.

The lack of returns from SBICs highlighted three challenges to venture investing generally. First, systematically producing outsized returns is a really hard thing to do, regardless of whether one is relying purely on private or publicly-subsidized funds. Second, scale matters. Many SBIC funds were severely undercapitalized, which made it difficult to construct a well-diversified portfolio of investments, and to attract talented investment professionals. Third, as is frequently the case when public funds are available in exchange for less flexibility, adverse selection was inherent. Fraud and malpractice were rampant, and many of the SBICs didn’t even invest in high-growth potential companies. Congress responded by applying more oversight, which compounded the problem by deterring the best investors.

Those challenges aside, the SBIC program made five major contributions to the development of venture capital in America—the significance of which should not be understated, particularly as many other nations continue to experiment with ways to spark innovation finance.

Framework: As Nicholas describes, SBIC “established a framework for thinking about the design of risk capital deployment in a context in which market-based venture capital was in limited supply.”

Competition: The proliferation of SBICs introduced more competition into a nascent venture industry.

Supported key companies: SBIC funds supported many high-tech startups in their formative years, including home runs like Intel.

Positive externalities: SBICs produced many positive externalities in emergent high-tech hubs, such as creating sufficient demand for the development of specialized service providers.

An entry point: The SBIC program provided an entry point for many talented, often young investors, into an industry that is notoriously closed-off. Legendary Silicon Valley firm Sutter Hill Ventures was created through two SBICs started by its founders William Draper III and Paul Wythes. Draper’s firm, Draper & Johnson Investment Company, was co-founded with Franklin “Pitch” Johnson, who went on to found many high-tech companies over his illustrious career. About the SBIC program, Johnson said “inexperienced guys like us couldn’t have raised money without the SBICs.” Hambrecht & Quist, one of the vaunted “Four Horsemen” (leading investment banks serving the high-technology industry and capturing the lion’s share of the tech IPO market up to the Dotcom bust), began as an SBIC.

The SBIC program continues to this day, supporting more than 300 investment firms each year. Although the program’s goals have shifted and to becoming more of a support mechanism for mezzanine finance, the program’s influential place in sparking a nascent venture capital industry during the 1960’s in the United States is unquestionable.

***

By the middle of the 1960s, the foundation of the venture capital industry had been cemented, as ARD proved the “home run model” of entrepreneurial investing could work, the limited partnership structure had been formally established in the industry by 1959, and a major government intervention in the SBIC program seeded a new generation of intermediaries to deploy risk capital into high-tech entrepreneurial ventures.

Silicon Valley and the Institutionalization of VC (late-1960s to late-1980s)

The third stage of venture capital spans the late-1960s through the 1980s—a period also defined by great leaps forward in semiconductors, personal computing, and the Internet. For venture capital, this era saw the “home runs model” repeatedly verified by a number of large exits, the establishment of “first tier” venture capital firms built around key personalities, and the emergence of investment patterns by style, sector, stage, and geography. This era also saw the development of a broader ecosystem as Silicon Valley scaled and various support mechanisms and enabling institutions flourished. Finally, the expansion of entrepreneurial finance was turbocharged by key changes in public policy—once again highlighting the critical role of the federal government in the development of the venture capital industry.

The ERISA “Prudent Man” Rule and Capital Gains Taxation

Two policy changes occurred in the 1970s that significantly improved the environment for entrepreneurship and venture capital to thrive—opening up both the supply and demand channels. Unlike with the SBICs, which were a form of direct government intervention in venture capital, these indirect “enabling” policies were meant to improve conditions for private actors to operate within.

By the mid-1970s, the venture capital industry was still fairly small, with no more than 30 firms of any real substance. But things changed dramatically after Congress amended the “prudent man” rule of the 1974 Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), which was implemented to protect individual pension and health plans. Under the act, pension fund managers (as passive investors) could be held liable for breaching fiduciary duty if the venture fund managers they invested in acted improperly. This had the impact of generally freezing out pension funds—an enormous source of institutional capital—from investing in venture capital.

“U.S Eases Pension Investing”, The New York Times, June 21, 1979.

In the year after the ERISA act was passed, pension fund investments into venture capital fell to zero, and was negligible over the next few years. But after Congress passed a 1979 amendment to relax the prudent man rule, pension fund commitments into venture funds skyrocketed. New pension fund commitments to venture funds doubled in the first year—making it the largest source of funding. By the mid-1980s, net new commitments into venture capital funds increased by a factor of ten, and pension funds were the single largest source driving this change.

A second major policy change during this time contributed as well—the lowering of the federal capital gains tax rate. In the late-1970s, the maximum marginal rate on capital gains was nearly 50 percent, but was reduced dramatically to 20 percent throughout the first half of the 1980s. While many organized interests contributed to this change in policy, in the book, Nicholas documents the venture capital industry’s central role among them.

However, it’s important to note that a reduction in the capital gains tax rate was likely not a major contributor to the expansion of the supply of venture capital, but more so, it worked to increase the demand for venture capital. For starters, many institutional investors are tax exempt. One influential academic study demonstrated that the growth in new venture capital commitments during the late-1970s to mid-1980s was driven the most by these investors, while investors most sensitive to tax change (high net worth individuals) actually saw their share of contributions decline. The implication from this and other research indicates that reductions in capital gains taxes work to increase the demand for venture capital by increasing the demand for venture capital (i.e., the supply of entrepreneurs).

These two major regulatory and tax changes in the late-1970s and early-1980s enabled the venture capital capital industry and the startups it supports to accelerate into a rapid growth phase into the 1980s and throughout the 1990s.

The Rise of Silicon Valley and the Emergence of Investment Styles

Nicholas details the evolution of venture capital in Silicon Valley in the 1960s and 1970s through the lens of three investment styles (people, technology, markets) and three prominent investors who typified those approaches (respectively, Arthur Rock, Tom Perkins, and Don Valentine).

Arthur Rock

Arthur Rock—a name that is synonymous with Silicon Valley—embraced the first of these approaches, building an investment strategy around exceptional people. A former Wall Street securities analyst, Rock is best known for brokering the deal that enabled the famed “Traitorous Eight” to leave Shockley Semiconductor to form Fairchild in 1957. His orchestration of the entire affair—in which Rock encouraged the eight men to both form a new company and to stay together as one team—is described in the book as being driven by Rock’s recognition of the group’s exceptional talent.

Rock co-founded the venture firm Davis & Rock with Tommy Davis in 1961. The fund invested in 15 companies over the seven-year life of the limited partnership, but two of them—Teledyne and Scientific Data Systems—generated exceptional returns. Davis & Rock turned just $3 million in deployed capital into more than $100 million in capital gains, making it one of the most profitable venture funds in history. Scientific Data Systems in particular was an example of the talent-centric approach favored by Davis and Rock, who were both enamored with Max Palevsky, the founder.

Both investors also made public statements that confirmed a desire to invest in the best people. In the book, Davis is quoted as saying “back the right people… people make products; products don’t make people.” Also, Rock once quipped “good ideas and good products are a dime a dozen … good people are rare… I generally pay more attention to the people who prepare a business plan than to the proposal itself.” This talent-centric approach may be the most dominant one in venture today.

When the seven-year term on their limited partnership expired in 1968, Davis & Rock wound down. Davis went on to co-found Mayfield Fund (a prominent Silicon Valley venture capital firm still today) as Rock made a pivotal investment as an individual. His 1968 investment in Intel was one of the most significant in the history of startup investing, not only because of what the company went on to achieve or the return it produced, but because of what it established as being possible in venture investing.

As laid out in the book, Rock’s investment in Intel provides four valuable lessons.

It was a continuation of Rock’s people-centric approach. The company’s founders, Gordon Moore and Robert Noyce, were members of the Traitorous Eight, who had maintained a relationship with Rock in the intervening years. It was Rock who they had reached out to about breaking away from Fairchild to start a new firm. Rock’s ability to syndicate a deal so quickly demonstrated the value he was assigned by Valley investors.

The investment demonstrated the importance of repeat founders, deal flow, and incentive compensation in a venture-backed startup. Moore and Noyce had credibility from the Shockley and Fairchild days, were quickly able to leverage a deal through Rock’s network, and could secure more favorable deal terms (equity) than less experienced founders.

Rock played a central role in firm governance by carefully shaping and leading the board, and as a mentor to the two founders.

The Intel investment was yet another validation of outsized returns in long-tail investing. The company produced wealth in the tens of millions for the founders and for Rock, and the success story drew additional talent to Silicon Valley and encouraged new entrepreneurs in the area.

Apple founder Steve Jobs (L) and early investor Mike Markkula (R)

Rock formed Arthur Rock & Co in 1969, the year after the Intel investment. Rock hired as a junior partner, Dick Gralmich, who was trained by Georges Doriot at HBS and would go on to co-found New Enterprise Associates (one of the most successful venture firms today). Arthur Rock & Co. made many investments, but one of the most consequential was the $57,600 into Apple Computer in 1978. Relying on his network, Rock was introduced to Apple by Mike Markkula—Apple’s first investor who Rock got to know from Markkula’s days at Intel. Venrock lead the half million dollar round, where Rock (who was skeptical of Steve Jobs) kicked in his share and joined the board. When Apple IPO’d two years later, that investment was worth $14 million—and in part, made Arthur Rock & Co. one of the highest returning venture firms in history (surpassing the same distinction given to Davis & Rock).

The next key figure in the development of the Silicon Valley venture business highlighted in the book is Tom Perkins, who in 1972 co-founded the venerable firm of his namesake along with Eugene Kleiner (also an engineer and one of the Traitorous Eight). Perkins—a protégé of David Packard from his time at HP—was fundamentally a technologist and his investment approach followed that theme. Because of this, Perkins took a more hands-on approach with his portfolio companies.

Kleiner & Perkins’s pitch to limited partners was threefold: exposure (access to networks and deal flow), judgment (established track records as investors), and ability to develop (as venture capitalists with operations backgrounds, they could “work with the management of fledgling investments” and to “understand the entrepreneur”).

Genentech founders Herb Boyer (L) and Bob Swanson (R)

The performance of its $8 million first fund was a critical step in setting the firm on the course to long-term success. Nearly a quarter of its investments earned multiples on initial investment of at least ten. Two of them were key: Tandem Computer and especially Genentech. KP Fund I returned 51% to investors on an annualized basis, compared with 8% on the S&P Composite. Excluding Tandem and Genentech would reduce the returns to just 16%. Absent these two home runs—in Tandem a $1.4 million investment that was worth $12.5 million at IPO in 1977 or $152 million if held until 1984, and in Genentech, a $200,000 investment that produced more than $300 million in value at IPO in 1980—Kleiner & Perkins would likely not have gone on to become the firm it became.

The Genentech story is an important one, and it produces four key lessons for the venture model, as Nicholas highlights in the book.

The firm’s ability to produce a rapid, high-value success in a risky endeavor—the production and commercial distribution of synthetic insulin—with immense social benefits was breathtaking. Perkins was instrumental in the founding, development, and ultimate success of the company.

Perkins advocated a “lean startup” approach, which meant outsourcing many parts product development through a network of specialists, experimentation, and staged investment (de-risking) as key milestones were met.

Genentech leveraged a wide range of capabilities in the local science base (primarily research and start scientists at the University of California San Francisco), which were foundational to the company. The ecosystem was pivotal.

Genentech shaped Perkins’s strategic and tactical approach as an investor—taking a very hands-on approach with early-stage, high-potential companies where technology was a central component. In fact, as Genentech became de-risked and later funding rounds were high-priced, Kleiner & Perkins chose not to participate.

I’m leaving out a lot of detail here, including the firm’s expansion of two additional partners in the late 1970s (Frank Caufield and Brook Byers and the subsequent renaming of the firm to Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers). That’s why readers need to pick up this book and have a read for themselves—my (already enormous) summary is meant to give a high-level overview of the book, with the idea of encouraging people to go deeper by picking up a copy for themselves.

The lesson here from the Tandem and Genentech investments is that Kleiner & Perkins was heavily involved with the formation and development of these companies from a very early stage—much aligned with a technology-first, value-adding venture capital firm.

Nicholas (2019), VC: An American History, Harvard University Press.

The third investor Nicholas profiles in the book is Don Valentine, who in 1972 founded Sequoia Capital. Whereas Rock was a “people picker” and Perkins was a hands-on technologist, Valentine was focused on finding markets with the greatest potential. As Valentine is quoted in the book: “my position has always been you find a great market and you build multiple companies in that market.” All of these investors focused on team, technology, and markets to a large degree, but they also leaned on one of these styles as a primary filter; exploiting opportunities in big markets was Valentine’s.

Unlike the pedigreed Rock and Perkins, Valentine was a tenacious New York City “street kid” and cut his teeth in the industry through sales—eventually leading that function at Fairchild Semiconductor and National Semiconductor. In these roles, Valentine “learned about companies that were addressing very large markets undergoing significant technological changes.” These experiences shaped his investment style and his eventual entry into venture capital.

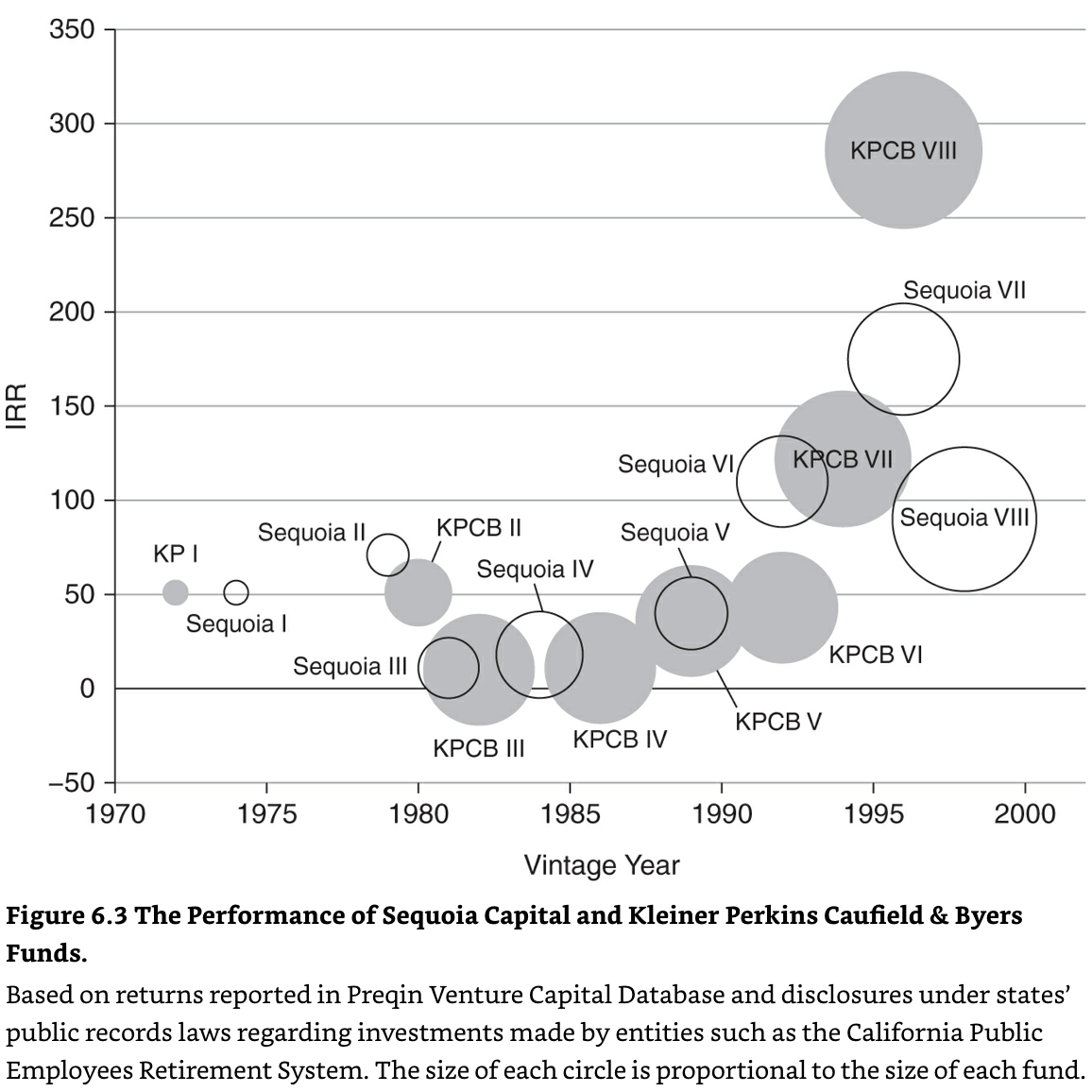

Sequoia started out as a venture arm of Capital Group, an influential investment firm based in Los Angeles. The firm was eventually taken independent by Valentine in 1975. Of course Sequoia has established itself as perhaps the most successful venture firm of all time, but early on, it was a few key successes that enabled future fundraising efforts and the deployment of additional capital into startup companies. This chart shows the returns on early Sequoia funds alongside Kleiner & Perkins (eventually, Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers), which demonstrate remarkably similar patterns.

Nicholas (2019), VC: An American History, Harvard University Press.

Two key early investments for Valentine were enabled by the networks he had built at Fairchild and National. A $600,000 investment in Atari in 1975 fetched Valentine a 4x multiple on capital a year later when the company was sold to Warner Communications for $28 million. Valentine’s network also brought him into contact with a former Atari engineer named Steve Jobs. Valentine connected Jobs with Mike Markkula (who he knew from their time at Fairchild), who he thought could provide Jobs and Wozniak with some much-needed sales help. Valentine participated in but did not lead the 1978 investment in Apple and he joined the company’s board. Prior to Apple’s IPO in 1980, Valentine sold his $200,000 investment for $6 million—a move that netted him a multiple of 30 on an investment in just a year and a half, but which is still seen as one of the biggest mistakes in venture capital history. This is all part of the risk-reward tradeoff, and as Valentine later remarked: “when the world badly wants what we have and is willing to pay us twenty or thirty times what we paid for it, our inclination is to let them take it.”

Tom Perkins (L) and Don Valentine (R)

Later on, Valentine’s $2.5 million investment for a 32% stake in Cisco in 1986 proved to be one of his most consequential of his career, not only because it was an investment in a critical internet-enabling technology at the cusp of the Internet explosion, but because Valentine would later remove one of the company’s founders—Sandy Lerner—in what was Nicholas describes as “an early example of the struggles faced by female founders in Silicon Valley high-tech firms.” As with Kleiner and Perkins before, Valentine ceased managing day-to-day operations of the firm within a decade or so to make way for the next generation of eager young VCs.

To close this subsection, I’ll use Nicholas’s words to summarize it, and as a setup to the next one:

“The region and the talent were not independent of each other, but developed together as Silicon Valley offered an unparalleled environment for the exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities…. Arthur Rock, Tom Perkins, and Don Valentine were all born and educated on the east coast, but they migrated to the west coast because it offered better prospects for new firm foundation… They supplied capital, provided governance support in terms of business plan development and access to contacts, and certified the quality of startups through their involvement…

…The Silicon Valley ecosystem consisted of high-growth companies like Fairchild Semiconductor, a pool of potential entrepreneurs eager to spin off their own startups, and professional managers whose training had been incubated inside large, high-tech firms. Founders intersected with venture capitalists and professional managers to create innovation powerhouses like Intel, Genentech, and Apple in time frames that were incredibly short. Venture-backed success stories like these were highly visible, and acted as catalysts to the development of additional startups and talent pools. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, the US venture capital industry was poised for an unprecedented takeoff.”

The Scaling of an Ecosystem and the Boom-Bust Cycle Comes to High-Tech

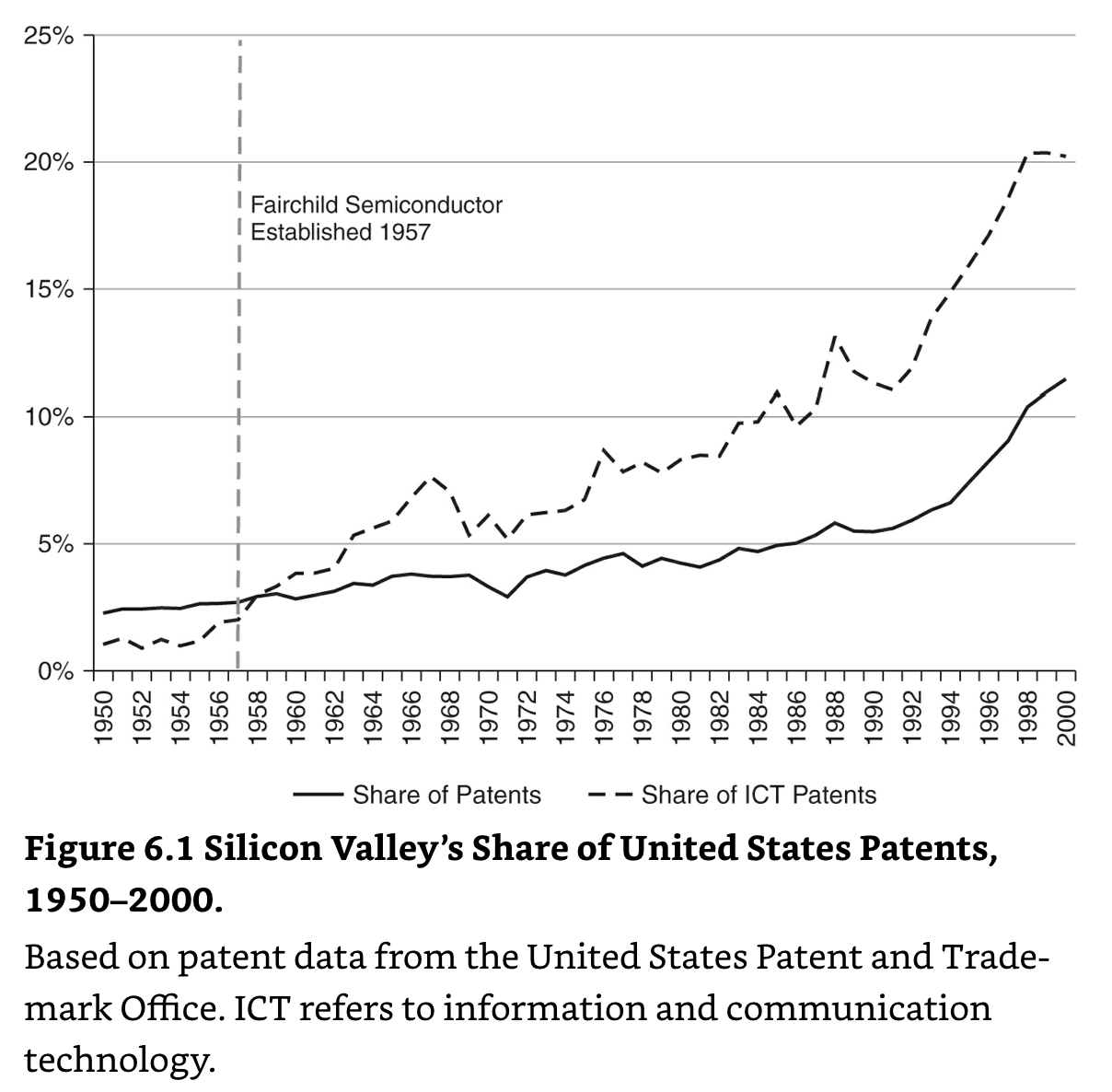

The roots of Silicon Valley as we know it stretch back more than one hundred years, but it wasn’t until the late-1960s, 1970s, and especially the 1980s, that it’s dominance as the leading global hub of innovation accelerated. That point is illustrated in a simplified way by this chart from the book, which shows The Valley’s share of patenting activity in the United States, overall and for information and communication technologies specifically.

Nicholas (2019), VC: An American History, Harvard University Press.

Silicon Valley’s dominance is a complex phenomenon involving many factors evolving over a very long period of time. There have been many books written on the subject, and therefore the subject is outside the scope of Nicholas’s book (and this post). However, Nicholas provides an apt summary of these “preconditions” for venture capital:

While the seeds of success enjoyed today by the larger, five-county San Francisco Bay area colloquially known as Silicon Valley were first sown in the late nineteenth century, the process of expansion, with respect to venture investing, owed much to the intersection of three main factors: direct and indirect benefits from universities, government military expenditures as a boost to high-tech, and a special cultural, legal, and physical climate. The formation of a strong innovation cluster created a demand for venture capital to finance unproven people, technologies, and products.

As the VC model of investing was further verified, a wider ecosystem in Silicon Valley grew around it. Law firms such as Cooley, Crowley, Gaither, Godward, Castro & Huddleson and Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati became highly specialized, dominating the venture capital and high-tech industries. The same is true for investment banks Hambrecht & Quist and Coleman & Stephens (two of the “four horsemen” mentioned before), which underwrote a substantial portion of high-tech public offerings in the 1980s and were a source of growth and mezzanine finance to pre-IPO companies. Silicon Valley Bank was founded in 1983 to provide banking services and venture debt to the rapidly expanding high-tech sector and the venture capitalists supporting it.

The “beanbag” conference room at Xerox PARC Computer Science Laboratory

Corporate venture capital also became more prominent during this decade. Though corporate venturing began to take off in the mid-1960s and produced a number of successes, this highly cyclical segment declined during the 1970s, where only about 30 entities remained active with $160 million in total capital. However by 1983, funds available to corporate venture capitalists swelled to $2.5 billion. One of these, Xerox Technology Ventures (XTV), was established in 1989 as a $30 million fund and produced a staggering 56% internal rate of return (IRR) compared to 14% for the average venture capital fund with the same vintage year. 3M also succeeded in doing what few corporations were able to during the 1980s—simultaneously generating a financial return (20% net IRR) while producing strategic complementaries with the business.

Direct government action returned with the launch of the Small Business Innovation Research program in 1982. The program sought to fill the “funding gap” for early-stage, high-tech startups that were (a) reluctant to cede substantial portions of equity to investors, and (b) not being served by existing programs such as SBICs (which began funding later-stage companies). The program, which deploys funds as grants or contracts to emerging small businesses through key federal government agencies, followed the staging structure of the venture capital model (Phase I proof of concept; followed by Phase II and III). The core objective of SBIR was to de-risk commercial opportunities in high-technology areas in an effort to attract more venture capital into the most promising ones. As Nicholas describes it in the book: “This was a government-funded platform designed to encourage creative technological development through the supply of seed money,” and later, he referred to it as a program that encouraged “technology prototyping.” The program is active today and is by most accounts a success in spurring experimentation in high-risk areas that are less attractive to private investors.

The 1980s also saw the further establishment of a hierarchy of venture capital firms, based on the returns they produced and the size of funds each could raise. Among the Tier 1 firms were Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, Sequoia Capital, Mayfield, and Greylock. Others that emerged include Battery Ventures, Accel Partners, and Draper Fisher Jurvetson, among others. Their reputations produced a virtuous cycle—attracting the best entrepreneurs (“stamp of approval”), producing the best returns, drawing in the best investors, and so on. Some firms specialized in various regions or industries, such as ARCH Venture Partners, which focused on commercializing innovations out of the University of Chicago and the Argonne National Laboratory, or firms like US Venture Partners and HealthCare Ventures—life sciences focused firms that drew inspiration from the outsized successes of Genentech and Amgen.

“The Coming Crisis In Home Computers”, The New York Times, June 19, 1983.

The 1980s was not without incident, as the high-tech sector experienced its first boom-bust cycle. The enthusiasm for venture capital and high-tech startups peaked by the early 1980s, just as the sector experienced a sharp downturn. Annual commitments into venture funds in the 1980s were more than twenty times what they had been a decade earlier. Easy money meant there was “too much capital chasing too few deals,” marketplaces became crowded, substandard companies were taken to public markets, and every newly minted MBA was rushing off to become a venture capitalists. A rash of company failures ensued. The burgeoning high-tech investment banks were all too willing to capitalize on venture mania and both they and the venture capitalists suffered repetitional damage. Don Valentine estimated that only half of companies taken public during the period needed to. As public markets lost confidence in high tech companies, the Nasdaq plunged 28% over an eighteen-month period in 1983 and 1984.

Similarly, venture capitalists were not entirely insulated from the leveraged buyout boom in the 1980s. As Nicholas notes:

“But while venture capitalists had domain expertise in early-stage investments, they also got caught up in later-stage activities—specifically, the leveraged buyout boom of the 1980s. Leveraged buyout transactions in the US economy increased almost eightfold from 1979 to 1988…

Although the expected return on an early-stage VC investment was higher than a leveraged buyout transaction, the long-tail distribution typical of early-stage investing made it considerably riskier. Add to this the need to deploy increasing amounts of capital coming through the influx of dollars from pension funds into VC (discussed in Chapter 5), and the appeal of leveraged buyouts is clear: they offered an opportunity to generate favorable returns in a short time frame. Whereas, in 1980, zero percent of VC investments were in leveraged buyouts, 23 percent were by 1986. Venture firms faced a demanding challenge: how to scale their activities while simultaneously maintaining a focus on early-stage investments.”

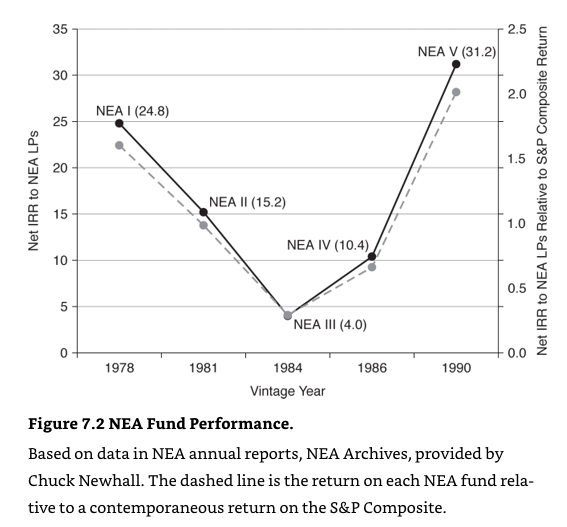

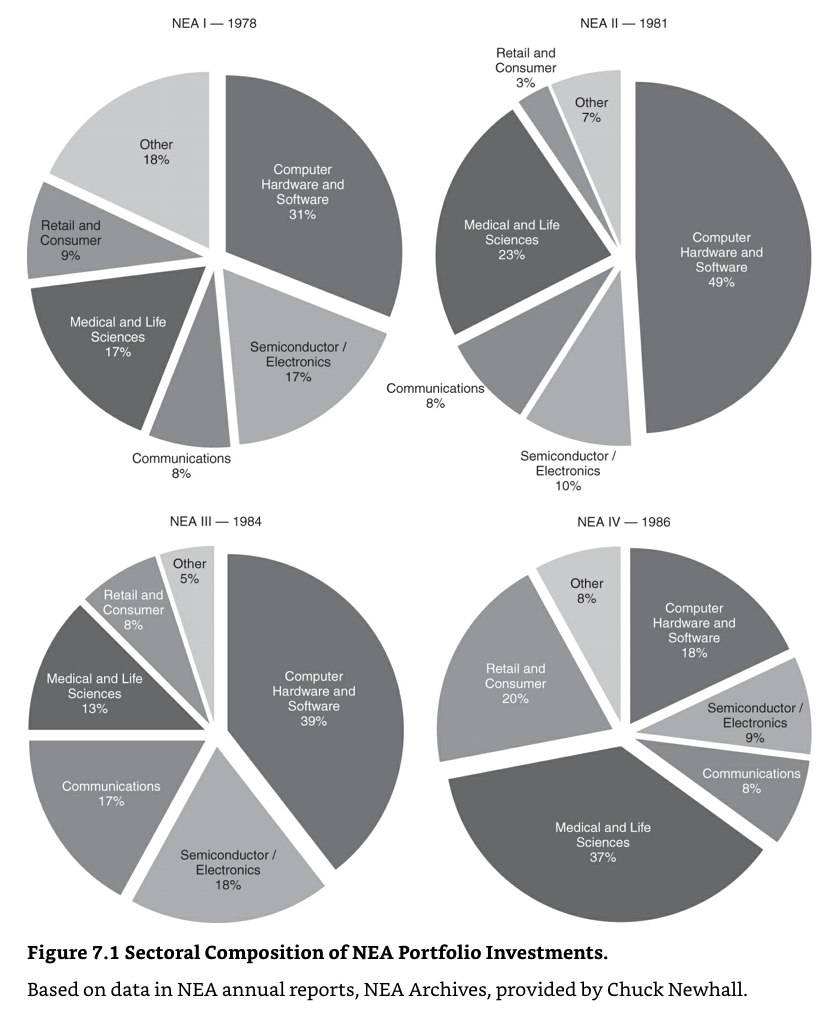

Though there will always be a debate about the relationship between the returns and the size of a venture fund, Nicholas highlights how this was successfully accomplished through the example of New Enterprise Associates (NEA). Founded in 1977 by Dick Kramlich (a protégé of Arthur Rock), Chuck Newhall, and Frank Bonsal, NEA successfully scaled across fund size, industrial focus, and geographic location. The figure here shows NEA’s returns for it’s first five funds, which increased in size from $16 million, to $45 million, to $126 million, to $151 million, and finally to $199 million by the fifth fund. The second chart shows industrial evolution of the firm, from a well-diversified first fund, to a shift towards computer hardware and software in the second fund, and eventually a specialization in medical and life sciences by the fourth fund.

The 1980s gave rise to next generation of great venture investors, including John Doerr. James Lally, and Vinod Khosla of Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, and Pierre Lamond, Michael Moritz and Doug Leone of Sequoia Capital, to name a few.

From left to right: John Doerr, Vinod Khosla, Michael Moritz, Doug Leone

The Origins of the Diversity Problem

If you haven’t noticed already, the imagery and discussion of individuals thus far have one dominant theme: white males. In fact, the only woman discussed in the entire book so far—Sandy Lerner—was a co-founder of Cisco who was fired by her male investors. Vinod Khosla, the only non-white person, is a male immigrant from India.

But the 1980s were not absent of successful women investors. Nicholas profiles a few of them. Ann Winblad, who in 1983 successfully exited Open Systems, a software company she co-founded, went on to start Hummer Winblad Venture Partners in 1989 and was one of the most important women investors of the era. Also profiled are healthcare investors Jacqueline Morby (TA Associates) and Ann Lamont, who has had an illustrious career as a founder of Oak Investment Partners, as well as investors Ginger More, Shirley Cerrudo, Deborah Smeltzer, Mary Jane Elmore, and Patricia Cloherty. Each left their mark on the venture capital business during this period.

Ann Lamont (L) and Ann Winblad (R)

And yet, the cognitive dissonance in the industry was astounding. As Nicholas describes in the book, the sentiment from inside the industry—from men and women alike—was that venture business was a great place for women. The data tell a different story. One academic research paper demonstrates that during the years 1990 through 2015, the women-share of venture capitalists fluctuated between just 6 and 9 percent. In other words, women’s participation was low and has remained low. Why?

Nicholas points to three potential factors. First, as Ann Winblad pointed out, the demands of the high-tech industry made it difficult to manage work and family—a responsibility that fell disproportionately on women. As she stated: “A lot of the successful men in the industry have no wives or children. It’s hard for women who have spouses or children to go it alone and put their business first. Men have clearly put their business first, and it’s easy for them, but a difficult focus for women.” Academic research affirms this “wage gap” dynamic more generally. Second, few women chose education and careers in the key feeders to venture capital—degrees in male-dominated STEM fields and lengthy careers in high-tech industries. Third, Nicholas claims that Harvard Business School (his employer!) deserves some of the blame. This is because Georges Doriot, the father of modern venture capital who trained a long lineage of future investors in the Valley, was an unabashed sexist. As Nicholas writes:

“Professor Georges Doriot… epitomized the School’s institutional sexism—largely barring women from taking his class even after women were officially admitted into the MBA program in 1963. Harvard MBAs became a mainstay of American VC, with recent data showing they still account for about a quarter of all venture capitalists at the top firms.”

***

Venture capital and its predecessors always funded the cutting-edge companies of their day throughout multiple eras in the 19th and 20th centuries, but by the early 1980s, VC and the booming high-tech industry became deeply linked. Producing outsized returns from long-tail investing over a short time period became more common by the end of the 1970s, but that was accelerated by the computing revolution taking place in the 1980s. While venture capital had little to do with the first wave of microcomputer firms, it was central to the second one.

As technological opportunities and capital were abundant, an ecosystem of support formed around the high-tech industry in Silicon Valley—as specialized service providers, differentiated investment approaches, and again, government policies played a role. The individuals who established the VC industry as we know it today moved aside for the next generation of great investors. These were predominantly white males, and though there were some examples of successful women investors, the diversity problem that continues in the venture capital business today was readily apparent.

The high-tech boom/bust and any venture capital industry mission creep into later stage, “private equity type” investments were relatively benign, but they highlighted three factors that will become apparent later on—the inherently cyclical nature of the sector, the tendency to deviate from core early-stage investment activities when capital is abundant, and to solicit funds from non-traditional investors (such as insurance companies that developed fund-of-funds).

The Rise of the Internet and the Dotcom Bubble (early-1990s to early-2000s)

The final era covered in the book spans the 1990s through the early-2000s. Because of its recency and the extremity of events that occurred, it is probably the most well-known period in the history of venture capital. The symbiosis between technology startups and venture capital further deepened. By the end of the 20th century, venture-backed companies accounted for 20 percent of publicly-traded firms in the United States and 32 percent of value in those markets.

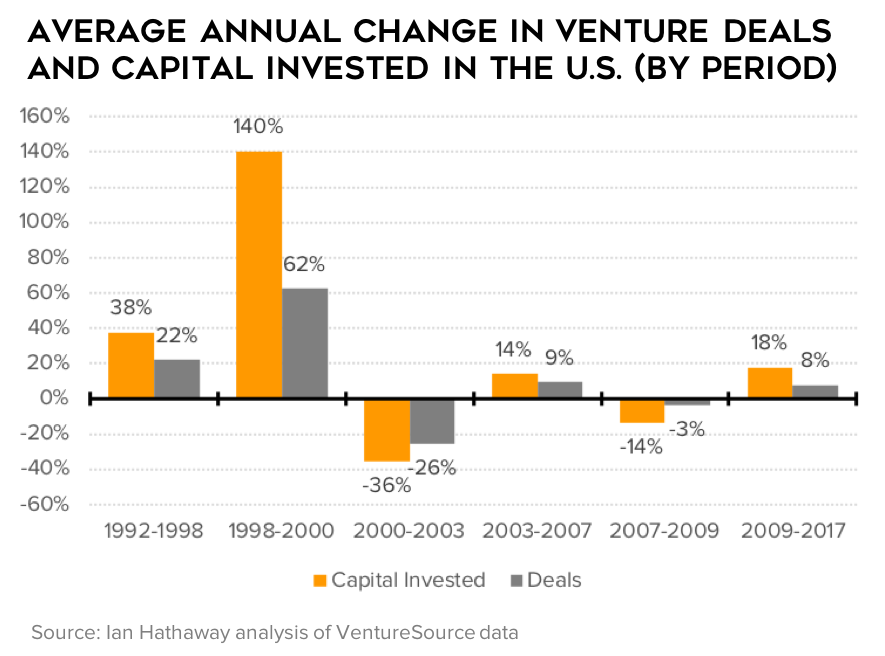

The defining feature was the scale and pace of growth achieved. For example, by 2000, there were more than ten times as many active venture capital firms than there had been just a decade and a half earlier. As I will show later, the growth rates in venture deals and capital invested during the 1990s dwarfs those seen even in a “hot” period like today—this is true even if one excludes the peak bubble years of 1999 and 2000.

A second defining characteristic of this period was the shift from investing in “real” technologies such as semiconductors, computers, medical devices, and biotechnology products, to the overwhelming dominance of software and internet services. A mentality of rapid expansion and control of consumer markets became pervasive, and would be a major contributor to the Dotcom bubble burst.

Third, the collapse in venture capital in the early-2000s was both rapid and substantial. New capital committed in venture funds between 2000 and 2003 fell by two-thirds. Venture capitalists and Silicon Valley entrepreneurs were discredited as losses in public markets accumulated. But as we already know, the tech sector would recover, and in fact, some of the most valuable companies today—including Amazon, Google, and Facebook—either persevered through or were launched in and around the meltdown.

The Digital Revolution of the 1990s

The information and communication technologies (ICT) revolution in the 1990s was made possible by a hundred years of advance in foundational innovations—from the vacuum tubes invented in the early 1900s that enabled advances in radio, telecommunication, radar, and mainframe computing technologies during and shortly after World War II, to the development of the transistor in the mid-1940s that made way for more powerful computing machines, the integrated circuit, and the microprocessor through the 1960s and 1970s, and finally to the introduction of the personal computer and advances in computer software and hardware in the 1980s.

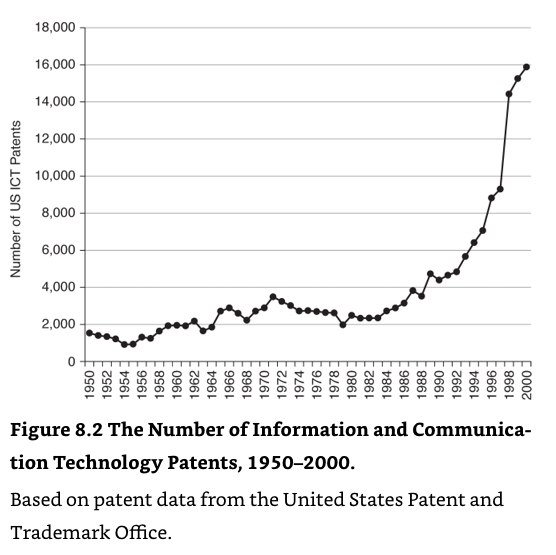

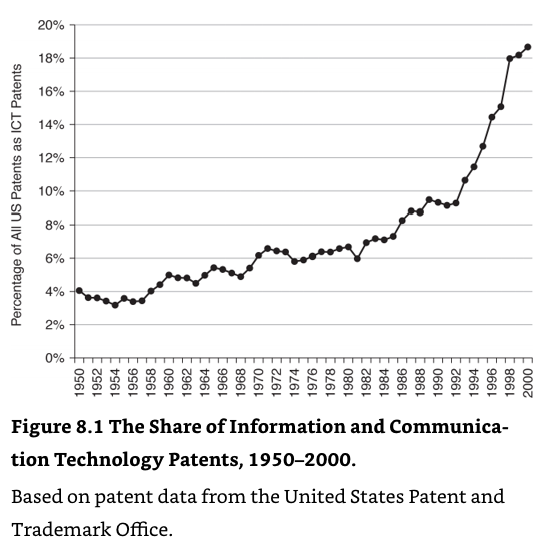

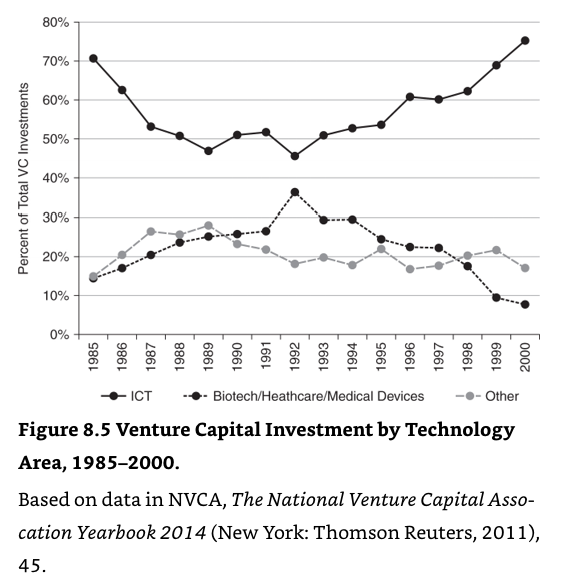

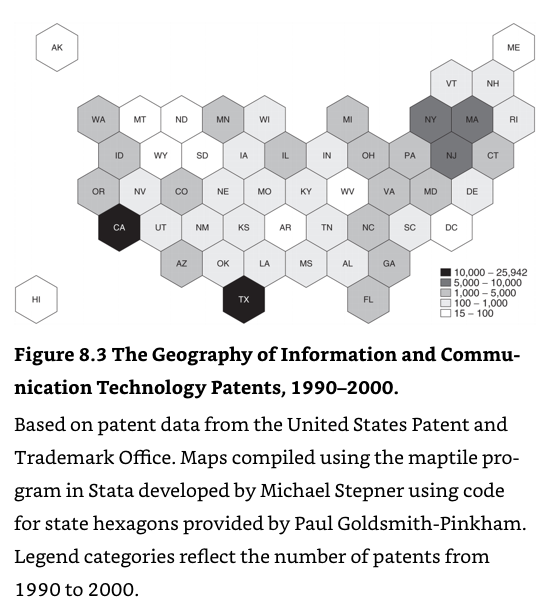

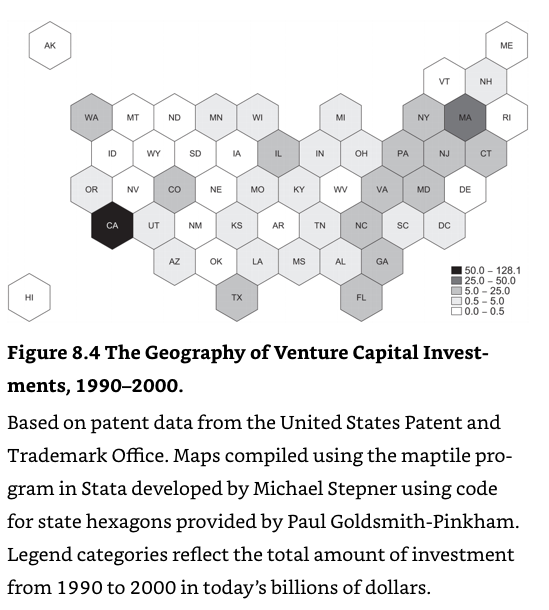

The stage was set for the digital revolution. As the data show, the level and share of patenting in ICT technologies skyrocketed in the 1990s, and the distribution of venture capital investments made an abrupt shift towards ICT from the early-1990s onward.

In addition to the explosive growth in information technology and venture capital activity, the data also show the substantial geographic concentration of these industries in places like Massachusetts, Texas, and especially California. As these maps show, venture capital investment in the 1990s was even more concentrated than was high-tech activity (as measured by patents). These trends are still very much alive today.

The major breakthrough, of course, was the arrival of the World Wide Web in the 1990s. Based on research and networking projects at the U.S. Department of Defense going back to the 1950s, a series of innovations funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF), the development of the World Wide Web (including TCP/IP and HTTP protocols and HTML programming language) by Tim Berners-Lee and colleagues at CERN in 1991, and the later privatization of the internet by the NSF in 1993, what would become a great experiment on human connectivity was now operational.

The diffusion of the internet was rapid. The number of internet hosts swelled from 313,000 in 1990 to 43.2 million in 2000. A team at the University of Illinois, backed by NSF funding, incorporated the web architecture into Mosaic—an internet browser that ran on UNIX and Microsoft operating systems. One of the Mosaic team members, Marc Andreessen, went on to found Netscape Communications in 1994 (and in later, in 2009, he founded the preeminent venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz). Web hosting and mail was operational by the mid-1990s, as were key programming languages (Java) and capabilities (Flash), and early forms of social networks (Geocities, Tripod). Finally, a major regulatory change—the 1996 Telecom Act—increased competition, opened up access to information networks across the country, and unleashed demand for the internet.

Venture Capital in the 1990s

The 1990s were a wild time for venture capital. According to data I’ve compiled from VentureSource (a leading provider of historical venture deals), the number of deals and capital invested grew rapidly. In 1996, the number of venture deals was twice what it was in 1992 and capital invested was three times what it was just four years earlier. Over the next four years, activity grew even more. In 2000, the number of venture deals was nearly 4 times compared with 1996, and capital invested was more than 11 times! All told, in the span of eight years (1992 to 2000), there were eight times as many venture deals and nearly 36 times the amount of venture capital invested!

Fueling this boom was an insatiable demand in public markets for tech stocks. According to data from University of Florida business professor Jay Ritter, there were nearly 1,400 U.S. tech IPOs between 1995 and 2000, or 51 percent of total IPOs. During the entire period, 58 percent of tech IPOs were venture-backed companies; in 1999 and 2000, 67 percent were. These figures are much higher than in the early-1980s tech boom, where the 397 tech IPOs between 1980 and 1985 accounted for just 35 percent of all U.S. public offerings. Among tech IPOs during that period, just 42 percent were venture-backed.

Unsurprisingly, many venture funds that deployed capital around this time performed very well, and the returns produced by the era are astonishing. The chart here shows the average and top quartile net return (IRR) for venture funds by vintage year between 1985 and 2000 (comparable data from the early-1980s was unavailable, but on an apples-to-apples basis, Nicholas writes that returns in the late-1990s were considerably higher).

Nicholas (2019), VC: An American History, Harvard University Press.

As the data show, both the average and outlier venture funds produced increasingly larger returns as the 1990s progressed, with vintages in 1995 and 1997 being the best performers, before dropping-off considerably by 1999 as the Dotcom bubble burst set in. Even so, aggregate returns produced by the entire venture industry in the 1990s were substantial. According to one academic study that compared returns across the entire venture industry with a public benchmark (the S&P Composite), venture capital produced returns slightly below in both the 1980s and 2000s, but were twice the public benchmark in the 1990s. Of course, venture is a heavily skewed (long right-sided tail) business, but even zooming in on those, the outliers in the 1990s stand out.

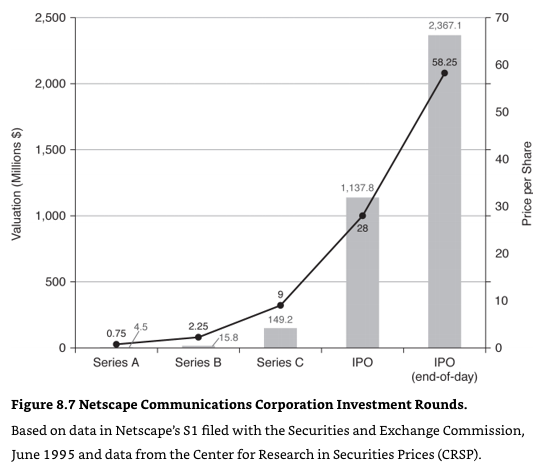

One of the outliers described in the book is Netscape Communications, and the critical role that John Doerr of Kleiner Perkins played in the success of the company. Netscape was founded in 1994 by Jim Clark and Marc Andreessen to commercialize the Mosaic browser they had helped to develop at the University of Illinois. Clark, who despised venture capitalists (allegedly referring to them as “velociraptors”), had a pre-existing relationship with Doerr from his time in Silicon Valley. Because of this, his admiration of Doerr’s investing acumen (he once called Doerr “the star at the most successful and influential venture capital firm”), and his belief that Doerr’s Silicon Valley network could draw talent, Doerr was the VC Clark chose to approach for help (Andreessen agreed).

On August 9, 1996, just sixteen months from founding, Netscape went public at a valuation of more than $1.1 billion. By the end of the first day of trading, the total shares outstanding were worth nearly $2.4 billion. On that day, Clark’s shares were worth $566 million and at the age of twenty-four, Andreessen’s were worth $58.3 million. The shares Kleiner Perkins held were worth $256.3 million. Prior to the $111 million in capital raised at the IPO, Netscape raised just $27 million in venture capital across three rounds between November 1994 and March 1995. Later, in March 1999, Netscape was taken private in an acquisition by AOL valued at more than $10 billion.

Nicholas (2019), VC: An American History, Harvard University Press.

According to Nicholas, the Netscape IPO was a significant catalyst to further innovations in internet services. Examples of these include: Microsoft’s acquisition of Vermeer Technologies to develop Internet Explorer (setting off the infamous “browser wars”); the January 1995 founding of Yahoo!, its subsequent IPO in April 1996, and ascent to being a billion dollar company by June 1997; and Microsoft’s $400 million acquisition of HoTMail in late-1997, just a few months after the product launched in July 1996 (Draper Fisher Jurvetson was HoTMail’s principal backer).

Finally, in what Nicholas deems “perhaps the most important venture capital investment from the standpoint of its effects on serial entrepreneurship” was PayPal. The company started out in 1998 as Confinity—founded by Max Levchin, Peter Thiel, and Luke Nosek—before merging with Elon Musk’s X.com in 2000. The merged financial services company became known as PayPal, and successfully went public in February 2002 before being acquired by eBay in August of that year. But, as Nicholas notes, the impact of PayPal is much bigger than the company itself:

“PayPal represented more than a high-tech company. It was a hotbed of entrepreneurial talent. Its impact was analogous to that of the Brush Electric Company on Cleveland in the 1880s and 1890s (see Chapter 2), the Federal Telegraph Company on Bay Area entrepreneurship in the early 1900s (Chapter 3), or Fairchild Semiconductor on Silicon Valley entrepreneurship in the 1960s (Chapter 6). Several PayPal founders and employees went on to start up other successful ventures (among them, YouTube, Yelp, LinkedIn, Tesla, and SpaceX) and became known as the “PayPal Mafia”—a moniker popularized by a 2007 Fortune article.”

Nicholas draws four lessons from these outlier investments in the 1990s:

Venture capital was heavily reliant on relationships, both in terms of capital deployed and for identifying investment opportunities. Investors primarily in the Valley used their strong social capital to secure the best companies and talent, and leveraged their considerable resources to ensure funded companies had the best chance at performing.

Uncertainty around the rapidly evolving information technologies remained high—as evidenced by the fact that many leading venture capitalists missed investments that seem obvious in retrospect. As Shane Greenstein of MIT noted: “many of the key innovations fell outside known forecasts and predictions and were unanticipated by established firms in computing and communications.”

The abundance of startup finance—and the lure of riches to be made in high-tech entrepreneurship—were powerful attractors of talented individuals who would become iconic entrepreneurs.

Private returns in the venture industry sometimes came at the expense of public markets, leading to a 1998 Fortune column to proclaim: “The dirty little secret of the venture business is that VCs can be enormously successful even though most of their portfolio companies may tank in the public markets,” which go well beyond the normal startup failures that are common. That same Fortune article estimated that 70 percent of the companies Kleiner Perkins took public between 1990 and 1997 lost money immediately after the first day of trading, and the 79 companies as a group returned 25 percent less than the NASDAQ benchmark.

This last point—that a rash of companies taken public that were of little value on public markets but earned private market investors (venture capitalists) a hefty catch—would be a theme that would play out intensely over the next few years, sullying the reputation of the industry and the companies it would back.

The Collapse and Its Aftermath

The extent of the Dotcom boom-and-bust can be illustrated by plotting data from the NASDAQ Composite. Between 1980 and 1995—the year Netscape IPO’d—the NASDAQ increased an average of 12 percent per year. By 1995, the NASDAQ cleared 1,000 for the first time and grew at an average rate of 24 percent through 1998, or double what it had been the previous decade and a half. However over the next two years, growth rates in the NASDAQ doubled yet again, as the index peaking at over 5,000 in March 2000—five times what it had been just five years earlier. The collapse was equally as dramatic, as the NASDAQ fell nearly 4,000 points, or a decline of 78 percent, before bottoming out in October 2002, just two and a half years after the peak.

This insatiable demand from public markets in the boom time changed the dynamics of the industry. As Nicholas writes in the book:

“Given that public markets represented one of the most important exit opportunities for venture-backed startups, the changing economic environment had a profound effect on the way that venture capitalists selected portfolio companies, thought about governance and business model development, and captured economic value from high-tech startups.”

In particular, the pace and scale of returns produced by the Netscape IPO created a frenzy around the very rapid deployment of capital to produce outsized returns.

Typically, capital from a fund would be deployed into portfolio companies over a three- to five-year period, to allow the companies to grow and generate returns by the end of the fund’s life cycle. During the late 1990s, however, several venture firms were deploying the capital within six to nine months. Benchmark III, a 1998 vintage year fund, was largely deployed in nine months into ICT and internet-based investments…

SoftBank Capital invested its entire 1999 $600 million Fund V within about twelve months, in forty-eight startups, mostly e-commerce ventures. Overall, internet startups accounted for about 68 percent of VC dollars invested in 1999.” [Editorial note: a friend who was involved with SoftBank at the time, disputes the veracity of the reporting around these events.]

Nicholas points to two problems with deploying capital so quickly. First, doing so did not allow VCs much time to conduct adequate due diligence. He references a 1999 Financial Times article, which reported investment decisions having to be made very rapidly for fear of missing out, even in as little as 48 hours in some cases. Because competition for deals was intense, contracts were often written with overly entrepreneur-friendly terms. The second problem with depleting capital so quickly is that it left little funds to follow-on investments in the best-performing companies. In short, as Nicholas summarizes, many “venture capitalists lost sight of the investment selection and governance emphases which had traditionally been hallmarks of the industry.”

The eventual fallout of the Dotcom bubble-and-burst was swift and severe. The National Venture Capital Association reported acquisition value of venture-backed startups fell 87 percent between 2000 and 2001, and the value produced through the IPO window fell 93 percent. Fundraising was scarce, and venture firms that did raise new funds had them significantly scaled back. Firms that withdrew carried interest as portfolio companies exited, saw “clawback” provisions activated by limited partners as it became evident the remaining companies would fail. Rather than focusing on making new investments, VCs were under tremendous pressure to focus attention on salvaging existing ones. Layoffs in The Valley mounted, and families were forced to relocate. After growing more than a percent per year for a decade, the population in the San Francisco Bay Area declined three straight years in 2002, 2003, and 2004. It wasn’t until the next wave of the digital revolution became established—in 2008—that population growth exceeded one percent.

There’s a lot of great content I’m leaving out in this chapter—including a fascinating case study of Pets.com versus Petstore.com, which typifies the intense competition around e-commerce startups at the time. But, the lessons are clear. The era demonstrated the cyclical nature of the venture capital model and presented an extreme view of long-tail investing. A number of painful lessons were learned in retrospect, and what emerged was the next wave of digital technology company-building and investing that has taken place over the last decade plus—emerging much stronger and steadier than the extreme swings of the Dotcom era.

Epilogue

Nicholas ends the book with the bursting of the Dotcom bubble—basically ignoring the entire last decade and a half of high-technology entrepreneurship and venture capital investing. On the one hand, this is a stroke of genius because it sends a strong message about respecting the arch of history—it is too soon to have a meaningful understanding for what’s happening right now, and by laying down a clear marker, Nicholas establishes that standard. This is an especially important point for many in the innovation business who are persistently wedded to the idea that “this time is truly different.” While each era has its own unique qualities, history repeats and many lessons from the past are useful for understanding the present. On the other hand, it is a bit of a missed opportunity to not have discussed at least some major themes emerging from this era, and place them in a historical context.

To finish, Nicholas writes an “Epilogue” to draw some major lessons from the book. I’ll quickly cycle through them.

Long-tail investing. The first is that the venture capital model relies on outsized returns from long-tail investing. Here, Nicholas includes an impressive chart (one that surely took a sophisticated hand to compile), which compares returns from the various eras of risk investing on a nearly apples-to-apples basis. It begins with returns from whaling voyages, the industrial era, the early players in the venture capital business, some top performing venture firms during the 1960s and 1970s, and a benchmark for the entire industry in recent decades. The data show that investing across these eras could produce similar returns, however, across these cases, it is the outliers that drive performance.

Nicholas (2019), VC: An American History, Harvard University Press.

Organizational form and strategy. The second big lesson from the book is outlining the emergence of organizational structure and strategy in venture capital—first as a closed-end fund adopted by ARD in the 1940s, eventually evolving into the limited partnership model by the late-1950s, which remains the dominant approach today. Organizational structure matters because it dictates what types of companies get funded.

The limited partnership model favors outsized returns on capital deployment over a short period of time. This helps explain why software and internet companies capture so much venture capital today, whereas companies in energy or life science are at a relative disadvantage. The terms “patient capital” and “deep tech” have recently entered the vernacular around startups and investing to signify companies that don’t fit the software/internet conditions, and alternative models of value-add have emerged—such as venture capital platforms (introduced by Andreessen Horowitz), accelerators (e.g., Y-Combinator, Techstars), and investment platforms such as Angellist and Kickstarter. Venture funds are growing ever larger, and it will be interesting to see if the historical tradeoff between performance and size is still a challenge, or if we’re truly in a new era.

Silicon Valley. The third big theme is the establishment of Silicon Valley as the dominant hub for venture capital and startup activity globally. While many have questioned the sustainability of Silicon Valley today—as poor urban planning has made cost and livability a major obstacle—Nicholas is quite bullish. Innovation hubs rise and decline. There is a long history of that, some of which is discussed in the book—such as New Bedford in the the whaling era, Cleveland and Pittsburgh in the industrial era. Because Silicon Valley is not tied to any geographic resource endowments, and because it’s cultural hallmark has been openness and flexibility to change, there is a degree of permanence not present in the others.

“Entrepreneurs and venture capitalists are attracted to Silicon Valley because of what economists describe as agglomeration advantages, the benefits to firms and people that grow when they are in close proximity to one another. Three factors help to keep Silicon Valley a vibrant venture capital and entrepreneurial hotspot: value-chain relationships among firms, the expertise resident in a deep high-tech labor pool, and the relatively free flow of intellectual ideas…

Importantly, these agglomeration benefits did not emerge in isolation or at an identifiable point in time, but rather arose over time through the long-run evolution of Silicon Valley. Combining to create indelible advantages were strong returns to scale from a deep-seated history of university-led innovation and human capital development; spillovers from military investment; pivotal firms such as Fairchild Semiconductor; a highly competitive but open entrepreneurial culture; amenable weather; pools of high-skilled immigrants; and a flourishing venture capital sector. New England did not have all of these. Nor did Cleveland, Pittsburgh, or Detroit.”

The complementarities between venture capital and the high-tech industry are a big part of Silicon Valley’s rise. Not to be forgotten in all of this—though outside the core function of this book—is the multitude of additional factors that made Silicon Valley possible, including key companies in radar and communications at the turn of the 19th century, and later in electronics; the open orientation of key individuals (e.g. Fred Terman, Bob Noyce) and institutions (e.g, Stanford, many corporations); and a mission-driven state in the U.S. government that allocated piles of cash to Silicon Valley tech companies at the heights of the Second World War and the Cold War that followed.

Government. Absent the unprecedented U.S. government appropriations on defense contacting and high-tech R&D, it’s hard to imaging that Silicon Valley would be what it is. U.S. government investments in science and innovation created many of the conditions that increased demand for venture capital (supply of entrepreneurs), which wouldn’t have occurred otherwise. In addition to “feeding the beast” of innovation via a mission-driven state, the U.S. government played a direct and decisive role in the development of venture capital. Two manifestations of direct government interventions highlighted in the book—the SBIC program, which played an important role in catalyzing the nascent venture capital industry in the 1950s and 1960s, and the SBIR program, which stimulated early-stage company experimentation beginning in the early-1980s and continues today. Two major policy changes in the 1970s—an amendment to the “prudent man” rule in the ERISA regulations that allowed pension funds to invest in venture capital, and the sharp reduction in the capital gains tax rate, which incentivized professionals to pursue startup opportunities by increasing the after-tax returns for doing so. Government investments in science and education—as profiled in the Genentech case—produce the intellectual property that supports much of high-tech innovation and entrepreneurship. Finally, the U.S. government’s liberalized stance towards high-skill immigration throughout the 20th century created a major source of inbound talent for Silicon Valley and has been a key source of its continued success (though is in danger today).

Diversity. One of the themes this book highlights—and part of the reason I used so much imagery in this post—is the glaring lack of diversity in the venture capital industry going back to its inception (including its predecessor forms of risk capital). Historically, venture capital has been an industry dominated by white men. Nicholas writes that at first the striking lack of diversity is a paradox because of the venture business’s reliance on embracing revolutionaries, visionaries, and because of its willingness to include some from nontraditional backgrounds, as well as immigrants. Instead, Nicholas attributes it to “some perceived disamenity” with hiring women driven by a “taste-based discrimination” in favor of men. A body of research has established strong homophily (sameness) in the venture business (something that is not uncommon in businesses that rely on social capital and decision making under uncertainty), which on account of starting out as a male-dominated business, would explain to some degree why that phenomenon continues today. Nicholas also points the finger at Georges Doriot, the “father of modern venture capital.” As a professor at Harvard Business School, Doriot trained many of the foundational venture capitalists that would shape Silicon Valley. Many others contributed to the “clubbiness” and “machismo” of Silicon Valley, but Doriot’s mark is clear.

***

Boom and Bust. Nicholas doesn’t specifically callout this topic in his concluding remarks, but I want to surface it here because as the book makes clear throughout: (i) the venture business is inherently cyclical, (ii) history shows these cyclical episodes can be extreme on the way up and the way down, and (iii) we are a decade into a record-setting venture capital bull market.