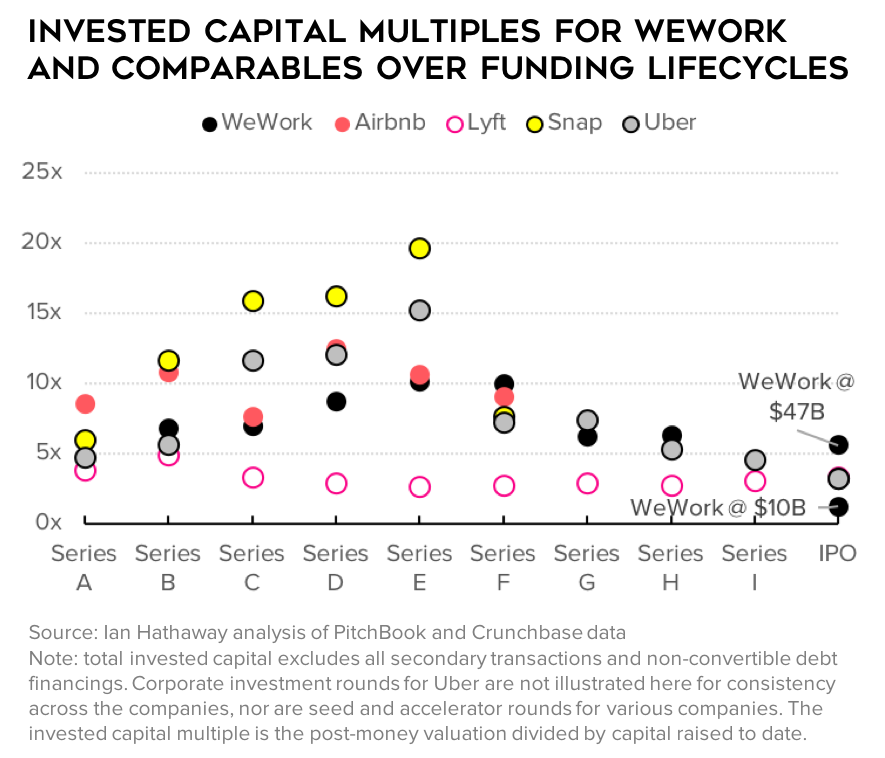

The initial target post-money valuation of $47 billion at IPO would produce an IC multiple of 5.6x, making WeWork the star of the group. However, if WeWork were to go public at a $10 billion valuation, then the IC multiple plummets to 1.2x—a middling return over the life of the company. For WeWork to achieve a multiple equal to the three-company average of 3.3x, it would have to reach a valuation of $28 billion. That seems unlikely now.

One question that rises to the surface is: is WeWork is too late in getting public? Given the beating that tech stocks like Lyft and Uber have taken in public markets since their IPOs, it’s fair to ask if investors are simply getting ahead of what’s to come. But even there, WeWork looks like an underperformer overall.

If one were to construct an “alternative IC multiple” which takes market capitalization of each of Lyft, Snap, and Uber today, and places that over their capital raised through IPO, they would still outperform what’s shaping up for WeWork—Lyft’s multiple would fall from 3.3x to 1.8x, Uber’s from 3.2x to 2.4x, and Snap’s would increase slightly from 3.3x to 3.7x. I realize these are not perfect comparisons, but they are directionally correct.

WeWork looks like a company that has been massively overvalued in private markets—particularly of late. Public markets look unprepared to continue that trend. Look no further than this Wall Street Journal article on Friday that shows SoftBank is prepared to prop-up a significant portion of the IPO. That’s wouldn’t happen if investor demand was there. It’s fair to question if the IPO happens at all. UPDATE (Sept 17): hours after this posted, the company announced plans to delay the IPO until at least next month.

WeWork wasn’t always this way. Throughout much of its lifecycle, the company exhibited rather modest growth in valuation to capital injection ratios. That changed dramatically in the last few years as SoftBank started pumping large quantities of equity and debt into the company, and gobbling up shares held by earlier investors and employees through secondary transactions. An examination of the data suggests the final round of financing in January—where SoftBank singlehandedly doubled the amount of capital raised by the company and doubled its valuation—is what may have thrown the whole thing off.

SoftBank, of course, looks like the big loser here. Not only did it single-handedly account for most of the latest-stage capital going into the company through both debt and equity—including the big round in January which may have undermined the entire pathway to a smooth IPO—but it also made a staggering $3 billion in stock purchases via secondary transactions. For more on what that means for SoftBank, read this from Chris MacIntosh.